This is a guest post submitted by Victor Archambault of US Radar, who is interviewing industry professionals who use Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR). In archaeology, GPR and other remote sensing technologies have been employed to create images of what lies beneath the ground ahead of (or instead of) excavation. Here is Victor's interview with Katy Meyers...

Dr. Temperance Brennan is a name that many TV show “Bones” fans know by heart but that is all just fiction and no one actually looks that closely to human remains. Right? Oh contraire, mon frere! There are real-life people that are just as interesting and fascinated in the mysteries that only human remains can tell.

Dr. Temperance Brennan is a name that many TV show “Bones” fans know by heart but that is all just fiction and no one actually looks that closely to human remains. Right? Oh contraire, mon frere! There are real-life people that are just as interesting and fascinated in the mysteries that only human remains can tell. I wanted to get some real world feedback on ground penetrating radar and how it is used out in the real world in various ways. I was able to interview Katy Meyers who runs a thriving blog at BonesDontLie while traveling the world, both learning the local culture and helping to unravel the secrecies of this thing we call “the past”.

Katy, what is your title and expertise?

I am currently a PhD Candidate at Michigan State University in the Anthropology Department. I also have an MSc in Human Osteoarchaeology from University of Edinburgh. My specialties include mortuary archaeology, digital archaeology, and geographic information systems.

** For those of you who don’t know what Osteoarchaeology is, it’s a branch of archaeology that deals with the study and analysis of human and animal anatomy, especially skeletal remains, in the context of archaeological deposits.

How did you first get interested in your field? Why?

My first interest in archaeology was as a kid- I spent most of my summers running up and down a gully near my house collecting historic bottles and fossils.

Are you familiar with ground penetrating radar and if so then how did you first learn of it?

I am familiar with GPR, and have seen it used for my work primarily in identifying lost graves in historic cemeteries, or determining where to excavate in a survey. I first learned about GPR while taking classes in [college].

Do you have any hands on experience with GPR?

No, never had the opportunity, but I have seen people do it first hand.

Is GPR worth using or are there other more effective methods or techniques?

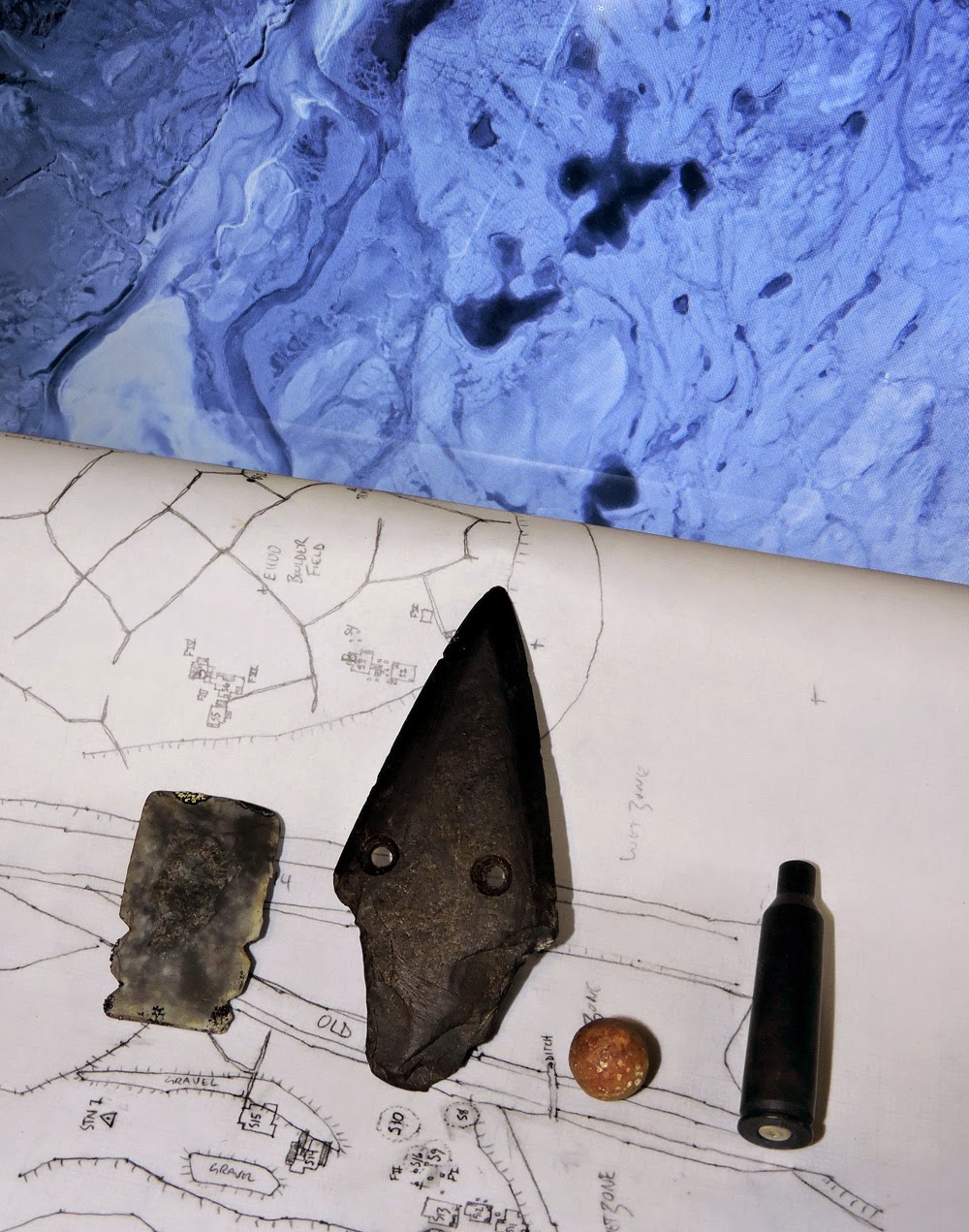

I think GPR is definitely worth using, although it should be combined with other methods such as ground survey, shovel testing and aerial photos.

Where do you see the future of GPR?

My hope would be that we would continue to create better tools for more accurate understanding of the earth, more portable, easier to use for those less experienced.

As a teacher, have you ever worked hands on with your students involving GPR or used its techniques in a classroom environment?

I’ve used GPR imagery from others’ work in order to help students understand survey techniques.

What do you like the most about your job?

I like solving puzzles using different lines of evidence. There are so many parts to archaeological work- historical texts, paintings, architecture, archaeology, human remains, rumors, stories, songs, environmental history, etc.

If you could travel back to the day you graduated high school and tell yourself one with about this field, what would it be and why?

Statistics is more important than you think- learn it early on instead of waiting!

I have to ask you something just to keep you on your toes so if you were a fruit, what would you be and why?

Black raspberry- ate them every summer when I was fossil hunting, always reminds me of home even though they are hard to get in other states.

It was a pleasure to get to know Katy and I hope you do visit her blog and if you would like more information about ground penetrating radar then please visit usradar.com

Follow Up Questions

You told me that you have seen GPR used first hand but did not delve much into that. Can you tell me what happened and what sorts of things you discovered through it?

We used it during a field school in Ohio to identify locations of prehistoric houses. We were able to locate an entire building and a garbage pit from the variations.

So I will admit I had no idea off hand what Osteoarchaeology is and had to Google it. Are there 3 – 5 specific things you find absolutely fascinating in this field that you get to do on a regular basis?

I really love learning who the average people were in the past. We hear about the ‘big men’ of history, but often do not hear about the rest of the people. My primary focus is burial practices, so how people chose to bury their dead and what this means about their religious/spiritual beliefs in afterlife and ancestors. I like studying that variation and interpreting what that means about their beliefs. It is pretty amazing how much you can learn from a single individual- age, sex, diseases, trauma, exercise or work habits, etc.

You touched lightly on field work but what kind of exotic places have you been able to visit and work in?

I have done work in Chillicothe, OH, East Lansing, MI, all over New York (state not city), a number of places in England and Scotland, Rome, Italy, and Giecz, Poland.

Have you ever had the opportunity to work on any “high profile” digs?

Kind of- I worked on a Polish cemetery that was pretty cool, and I did the cremation excavation for Isola Sacra in Rome.

I know many people out there have seen the TV show “Bones” and would you say you roll your eyes at the show or geek out at watch every episode? Also, how close are they to reality or has it been done up just for a TV audience?

I actually helped with the osteoarchaeology for one of the episodes! Yes, it is more fiction than fact- they really stretch how much you can actually learn from the skeletons. I have a bad habit of yelling at the TV. However, I did really like the first few seasons- it got too emotional dramatic though and I gave up on it a few years ago.